Improving performance of lockless data structures

As multi-core computer systems grow in number of processors and processor cores one of the largest challenges in software is to scale the performance of data structures to properly utilize the potential concurrent performance that modern hardware offers. To tap into this potential performance data structures need to be able to execute multiple operations at the same time with minimal synchronization between threads or else the hot path of the code risks stalling threads and wasting processor cycles. Below is probably the most common solution you’ll find.

class Foo {

private:

std::shared_mutex rw_lock; // Read-write lock.

std::vector<int> data; // Some data to protect.

public:

void broadcast(int index) {

// Shared lock.

std::shared_lock<std::shared_mutex> shared(rw_lock);

return data[index];

}

void Change(int change) {

// Exclusive lock

std::unique_lock<std::shared_mutex> exclusive(rw_lock);

data.push_back(change);

}

Figure 1. Example C++ read-write lock.

Traditional locking strategies including read-write locking doesn’t scale beyond a couple threads. It’s hard to find servers that have less than 4 cores and quite common to find many with 16 or more. Most data structures scale poorly beyond 4.

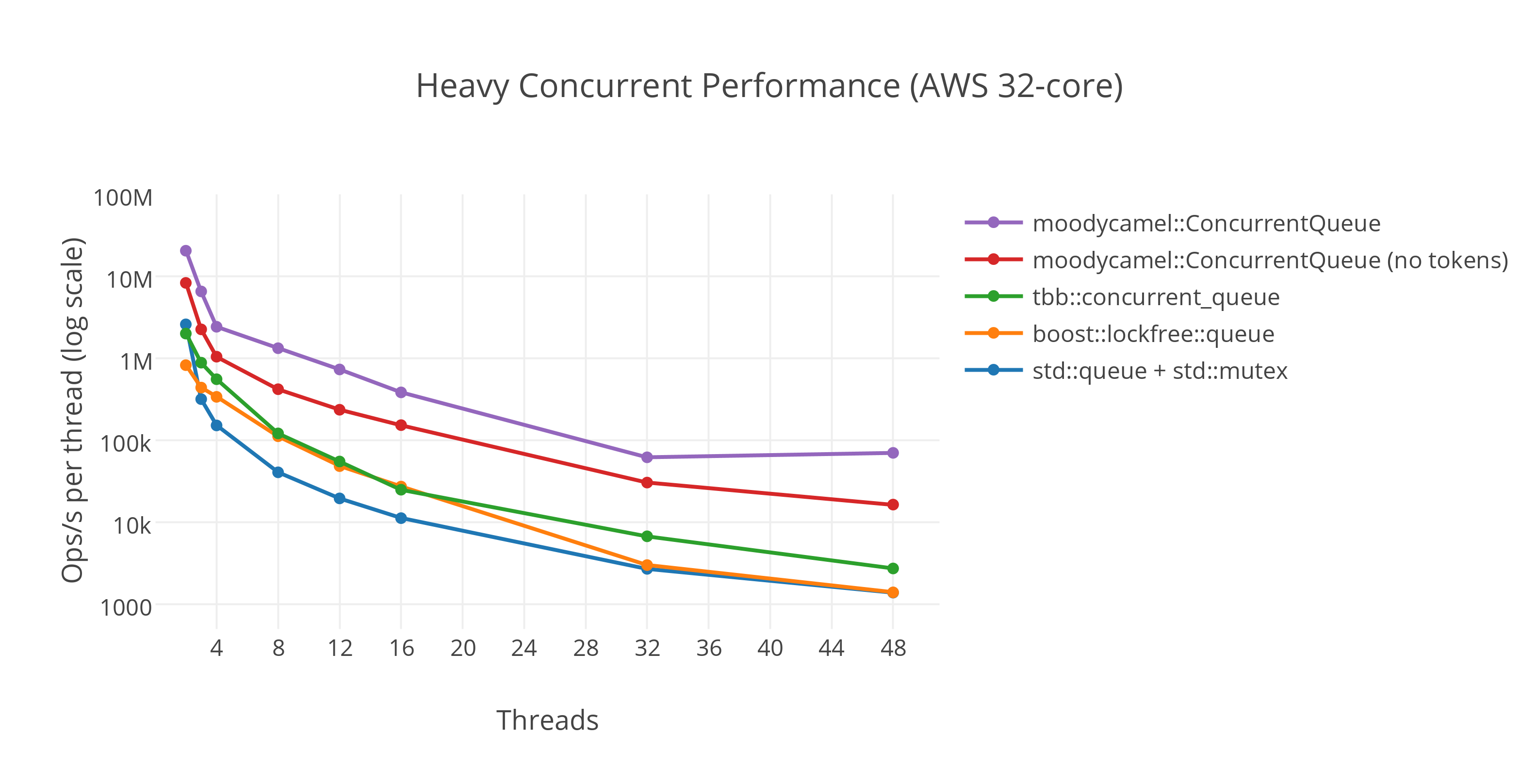

Figure 2. A fast general purpose lock-free queue for C++ by Cameron.

Figure 2. A fast general purpose lock-free queue for C++ by Cameron.

Even using modern lock-free data structures performance starts to show signs of degrading significantly after 4 threads. Figure 2 shows less than 1 million operations/second at 12 threads. Even the Intel(R) Threading Building Blocks library optimized for Intel(R) processors written by Intel(R) themselves suffer from scalability degradation.

In a previous post I published benchmark results showing my octane project reaching 18.4 million plaintext requests/second and 15.6 million JSON requests/second. Octane is able to achieve this kind of throughput by reducing inter-thread synchronization so that each thread runs independently. Since main system memory (RAM) is a shared resource across all CPU cores one way octane does this is by reducing calls to malloc() that may under the hood trip on lock contention during allocating, resizing or freeing of memory. Using memory allocators like TCMalloc or JEMalloc can help because they create per-thread memory pools. While these reduce synchronization penalties they don’t remove them entirely. The less memory octane allocates and the more it reuses the less threads will stall each other. This is extremely key at this high of throughput.

Figure 3. Octane benchmark results on a 20 hardware thread Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5-2660 v3 2.60GHz system over a 20GbE network.

Figure 3. Octane benchmark results on a 20 hardware thread Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5-2660 v3 2.60GHz system over a 20GbE network.

Using efficient data structures will be extremely important to keep the performance shown in Figure 3 as I add more features to octane.

Multiversion concurrency control

Whether it’s an on-disk or in-memory data structure the same concurrency challenges exist. Some storage libraries and database engines implement handling multiple concurrent transactions using a technique called multiversion concurrency control (MVCC). Each transaction gets a point in time consistent view of the database from the time the transaction began. The database internally manages multiple versions of the database to support this ability and cleans them up when there are no longer running transactions associated with a version. Some examples of databases or storage libraries with MVCC implementations are Berkeley DB, Couchbase, CouchDB, HBase, LMDB, MariaDB (XtraDB), MemSQL, Microsoft SQL Server, MongoDB (WiredTiger), MySQL (InnoDB), Oracle v4+, PostgreSQL and SAP HANA to name a few.

Figure 4. Apache Mavibot™ MVCC BTree update.

Figure 4 shows how Apache Mavibot™ copies the BTree root page to apply changes. Instead of locking the access of the data itself you can give copies of the pointers to the data to each reader or writer. Readers can proceed to read without having to acquire a lock. The pointer pointing to the master record only needs to be updated by swapping it’s pointer to a new pointer that has all the changes already written. This reduces a lot of inter-thread synchronization.

The benefits are that write operations do not block reader operations and read operations do not block write operations. This allows threads and CPU cores to proceed unrestricted from each other.

Reclamation

The next performance bottleneck now shifts to the reclaiming memory phase to clean up all the unused copies. Checking if memory is unused and reclaiming it can be costly and can re-introduce significant synchronization between threads in the hot path of the code.

The Swift programming language doesn’t use the traditional garbage collector style memory management. Swift uses a reference counting mechanism called ARC (Automatic Reference Counting). Reference counting has high overhead and scales poorly with data structure size.

There has been some research around 3 reclamation schemes that are worth considering.

- Quiescent-state-based reclamation (QSBR).

- Epoch-based reclamation (EBR).

- Hazard-pointer-based reclamation (HPBR).

QSBR and EBR are blocking schemes which use a grace period to identify when all memory from all threads before the grace period can be reclaimed. These 2 schemes force threads to wait for other threads to complete their lockless operations before reclamation happens in the grace period. Failed or delayed threads can potentially prevent freeing memory and the process will eventually fail allocating memory. These are very similar to the read-copy-update (RCU) mechanism. QSBR is lighter weight than RCU but it requires each thread to indicate a quiescent state (threads must pass a checkpoint) which is application specific. EBR is a more convenient alternative to QSBR. With EBR you indicate the critical section instead of indicating an application specific quiescent state. EBR’s book keeping is invisible to the application programmer. EBR is slightly slower than QSBR due to more frequent checking.

An algorithm using HPBR sets a hazard pointer to shared memory it wishes to use and then checks if it has been removed by other threads. If the memory has not been removed it is safe to be used. When a thread wishes to release memory it adds it to a private removal list. When the list grows to a predefined size it checks each entry in the removal list for hazard pointers. If an entry lacks hazard pointers it is safe to reclaim the memory. The sequence is the following.

- Remove the node from the data structure.

- Iterate the list of hazard pointers.

- If no hazard pointers were found, delete the node.

Final thoughts

These algorithms are quite complicated to get correct but this shows the challenges of scaling to the processing power available on modern computer processors. I suggest reading the references below for more information and examples.